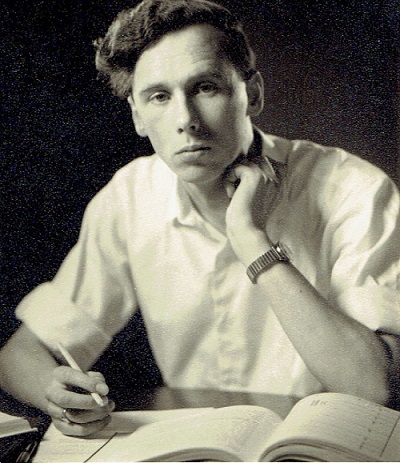

St Peter’s College alumnus, Terence Meaden, was at Oxford for almost a decade and worked alongside Dr Kurt Mendelssohn among others. He is the co-author of Going for Cold, the Springer biography of Mendelssohn and here reflects upon his time at Oxford.

As an undergraduate I enjoyed three years in Oxford (1954-1957), including lectures and practical work at the Clarendon. Among the lecturers were Professor A Lindemann (Lord Cherwell), Dr Kurt Mendelssohn and Dr Nicholas Kurti extolling the virtues of research on the properties of liquid helium and superconductivity. In my finals year I developed an ambitious aim to join one of the teams myself, so I wrote a careful letter to Mr T C Keeley—managing director of the Clarendon—expressing an interest in post-graduate research if the opportunity arose. Soon after taking finals in June 1957, I received a letter from Kurt Mendelssohn inviting me for interview, and asking whether I was interested in embarking on a DPhil research project.

His letter began: ‘I intend to start in the coming academic year two research projects in one of which you may be interested. The first concerns the investigation of the electric and thermal properties of the transuranic elements in metallic form. Plutonium and neptunium are now available and there is a hope that sufficient quantities of americium will be available in the not-too-distant future. This work will be coupled with the investigation of other heavy elements, in particular thorium and uranium.’

A few days later I arrived for interview, got accepted, and was being shown the cryostat that the workshop had built to Dr K. Mendelssohn’s design for use with thorium and uranium. KM added that there would be a second cryostat at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell where work on the highly toxic radioactive metals plutonium and neptunium would be done using the protection of a glass-sided glove box. Senior scientific officer Dr James A Lee would be my supervisor—a convivial lovely man and first-rate scientist. I would take my newly-acquired knowledge of liquid-helium cryogenics to Harwell in this way.

Working at first in Oxford I took the cryostat and supporting equipment to the trial and functioning stages when studying the electrical properties of uranium and thorium down to liquid helium temperatures. Gradually, as I got to know KM better, I found what a brilliant all-rounder he was in general conversation. He was willing to discuss almost anything with a kindly mindset and optimistic worldview. Born in 1906 he had followed an ambitious path in Germany, and from 1933 pursued it in Oxford to immense scientific advantage. His investigations had been pioneering and profitable academically. He assured me that many scientists reach a peak of excellence in their late twenties and thirties, and I should bear that in mind. ‘Grasp the nettle,’ he said, meaning tackle the inevitable difficulties boldly, directly—much as he had done. This was an inspiring start to years of mutual respect and cooperation.

By summer 1960 he judged that I had done enough research at Harwell and Oxford for my thesis and urged me to write it up. I was examined a year later.

The next project was to build a new cryostat featuring a quantity of rare helium-3 gas so that at the Clarendon we could take specimens of radioactive plutonium and neptunium protected in sealed containers to lower temperatures than could be realised with helium-4, namely 0.3 Kelvin—record low temperatures for these dangerous metals. In 1963 after nine years in Oxford I decided to move on, and asked KM whether he would recommend me to Professor Louis Weil for a faculty position in the physics department of the University of Grenoble and he kindly obliged. I became an assistant professor at a French university and after a while was engaged and married to a French secretary – in 2022 we shall celebrate 57 years of marriage. After Grenoble, I went to Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, and by age 34 was a tenured associate professor with four PhD students. Many years later, when back in Oxford I did six years part-time undergraduate archaeology and two years for a master’s degree in applied landscape archaeology at the Department of Continuing Education. Numquam sero. It’s never too late.

I count myself lucky to have spent formative years with pioneering researchers in advanced experimental physics and I thank Dr Mendelssohn for the opportunity. For the life story of Dr Mendelssohn, 1906-1980, refer to the biography Going for Cold published by Springer.