Scientists at Oxford have found a simple and effective way to control magnetism at the nanoscale, opening a new route to engineering advanced materials for next-generation low-energy technologies. This advance centres on antiferromagnets – a unique class of quantum materials that behave very differently from everyday magnets.

Antiferromagnets are composed of tiny atomic magnets that are aligned oppositely and this small change enables very unique properties. They can switch very little energy at extremely high speeds – 100-1000 times faster than today's silicon-based devices. Yet one major obstacle has held them back: their magnetic states tend to break up into unpredictable patterns, called ‘domains’, that are difficult to manipulate reliably.

'Antiferromagnets could enable technologies far beyond the limits of silicon,' says Dr Hariom Jani. 'The real challenge has been control – finding a way to design their domains predictably at the nanoscale. Achieving precise nanoscale control finally overcomes a key barrier that has held back antiferromagnets, bringing these promising materials much closer to practical use.'

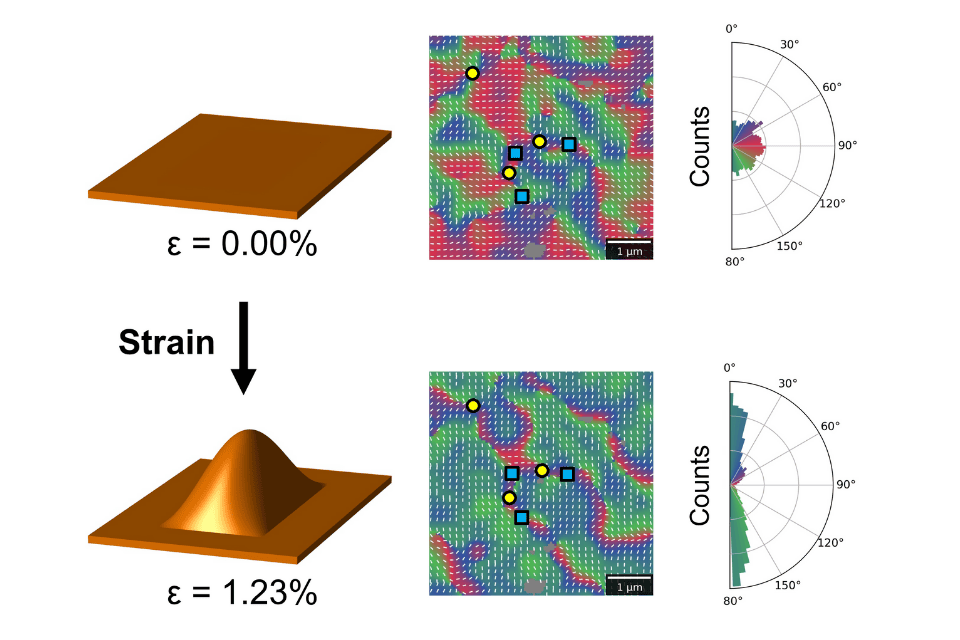

In a study published in ACS Nano, the Oxford team led by Dr Hariom Jani and Professor Paolo G Radaelli tackled this challenge by demonstrating that the key to this control lies not in magnetic fields but in something far simpler: strain. They worked with free-standing membranes of the classic antiferromagnet hematite (α-Fe₂O₃) – the purest form of iron oxide in rust – that are highly flexible and can be bent by over 1000 times their thickness. By bending the membranes to apply controlled in-plane strains, they discovered that they could reconfigure the magnetic order at room temperature with remarkable precision.

Using high-resolution X-ray microscopy at the PolLux beamline of the Swiss Light Source, the team directly observed how the magnetic domains evolved as the membranes were gently stretched. They found that controlled strain provides a clean and reversible way to reconfigure the material’s magnetic state. A uniform stretch could shift the magnetism from pointing out of the membrane plane to lying within it, while directional strain introduced a uniaxial preference that helped align the nanoscale domains toward a more uniform configuration. Importantly, topological features such as merons and antimerons, which are whirling magnetic 'tornadoes', remained stable even under large deformations, showing that strain can reshape the magnetic landscape without damaging these structures — a key requirement for future devices.

'The combination of novel materials design and state-of-the-art experimental techniques allows us to tune the properties of quantum materials in new and impactful ways,' says Dr Jack Harrison, who undertook this project as a DPhil student with the Department of Physics. 'We’ve demonstrated that we can delicately tune the different magnetic anisotropies in hematite by leveraging the flexibility of antiferromagnetic membranes. Reproducibly straining these membranes will allow us to design devices that require various magnetic alignments and properties from a single platform.'

The implications of this advance are far-reaching. Strain offers a practical, versatile ‘control knob’ that could be built into the material during fabrication or embedded in future devices through piezoelectric layers that expand or contract on demand.

'This would allow electronic and magnetic components to dynamically reshape their internal magnetic landscape with extremely low energy input', says Professor Paolo Radaelli.

Room temperature control of axial and basal antiferromagnetic anisotropies using strain, J Harrison et al, ACS Nano 2025, 19, 50, 42118–42127.