Physicists at the University of Oxford have unveiled a pioneering method for capturing the full structure of ultra-intense laser pulses in a single measurement. The breakthrough, published in close collaboration with Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich and the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics, could revolutionise the ability to control light-matter interactions. This would have transformative applications in many areas, including research into new forms of physics and realising the extreme intensities required for fusion energy research. The results have been published today in Nature Photonics.

Ultra-intense lasers can accelerate electrons to near-light speeds within a single oscillation (or ‘wave cycle’) of the electric field, making them a powerful tool for studying extreme physics. However, their rapid fluctuations and complex structure make real-time measurements of their properties challenging. Until now, existing techniques typically required hundreds of laser shots to assemble a complete picture, limiting our ability to capture the dynamic nature of these extreme light pulses.

RAVEN: novel single-shot diagnostic technique

The new study, jointly led by researchers in the University of Oxford’s Department of Physics and the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich, Germany, describes a novel single-shot diagnostic technique, named RAVEN (Real-time Acquisition of Vectorial Electromagnetic Near-fields). This method allows scientists to measure the full shape, timing, and alignment of individual ultra-intense laser pulses with high precision.

Having a complete picture of the laser pulse’s behaviour could revolutionise performance gains in many areas. For example, it could enable scientists to fine-tune laser systems in real-time (even for lasers that fire only occasionally) and bridge the gap between experimental reality and theoretical models, providing better data for computer models and AI-powered simulations.

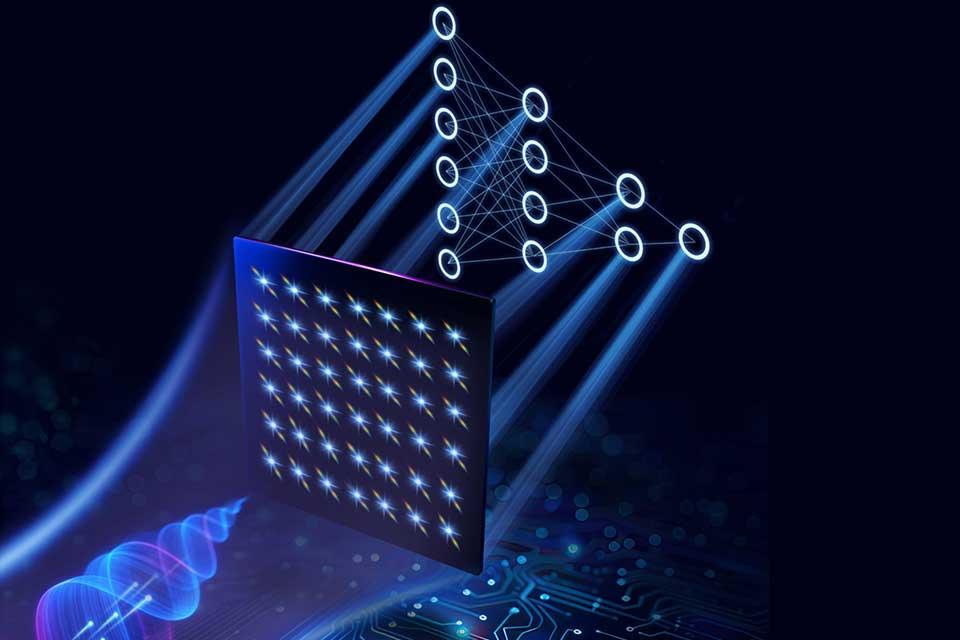

The method works by splitting the laser beam into two parts. One of these is used to measure how the laser’s colour (wavelength) changes over time, while the other part passes through a birefringent material which separates light with different polarisation states. A microlens array – a grid of tiny lenses – then records how the laser pulse’s wavefront, or its shape and direction, is structured. The information is recorded by a specialised optical sensor, which captures it in a single image from which a computer program reconstructs the full structure of the laser pulse.

Lead researcher Sunny Howard, PhD researcher in the Department of Physics, University of Oxford and visiting scientist to Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich, said, ‘Our approach enables, for the first time, the complete capture of an ultra-intense laser pulse in real-time, including its polarisation state and complex internal structure. This not only provides unprecedented insights into laser-matter interactions but also paves the way for optimising high-power laser systems in a way that was previously impossible.’

Characterising spatio-temporal couplings

The technique was successfully tested on the ATLAS-3000 petawatt-class laser in Germany, where it revealed small distortions and wave shifts in the laser pulse that were previously impossible to measure in real-time, allowing the research team to fine-tune the instrument. These distortions, known as spatio-temporal couplings, can significantly affect the performance of high-intensity laser experiments.

By providing real-time feedback, RAVEN allows for immediate adjustments, improving the accuracy and efficiency of experiments in plasma physics, particle acceleration, and high-energy density science. It also results in significant time savings, since multiple shots are not required to fully characterise the laser pulse’s properties.

The technique also provides a potential new route to realise inertial fusion energy devices in the laboratory – a key gateway step towards generating fusion energy at a scale sufficient to power societies. Inertial fusion energy devices use ultra-intense laser pulses to generate highly energetic particles within a plasma, which then propagate into the fusion fuel. This ‘auxiliary heating’ concept requires accurate knowledge of the focused laser pulse intensity to target to optimise the fusion yield, one now provided by RAVEN. Focused lasers could also provide a powerful probe for new physics – for instance, generating photon-photon scattering in a vacuum by directing two pulses at each other.

Co-author Professor Peter Norreys, also from Oxford’s Department of Physics, adds: ‘Where most existing methods would require hundreds of shots, RAVEN achieves a complete spatio-temporal characterisation of a laser pulse in just one. This not only provides a powerful new tool for laser diagnostics but also has the potential to accelerate progress across a wide range of ultra-intense laser applications, promising to push the boundaries of laser science and technology.’

Co-author Dr Andreas Döpp from Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich and visiting scientist to Atomic and Laser Physics at the University of Oxford adds: ‘Shortly after Sunny joined us in Munich for a year it finally “clicked” and we realised the beautiful result underpinning RAVEN: that because ultra-intense pulses are confined to such a tiny space and time when focused, there are fundamental limits on how much resolution is actually needed to perform this type of diagnostic. This was a game changer, and meant we could use micro lenses, making our setup much simpler.’

Looking ahead, the researchers hope to expand the use of RAVEN to a broader range of laser facilities and explore its potential in optimising inertial fusion energy research, laser-driven particle accelerators and high-field quantum electrodynamics experiments.

Single-shot spatiotemporal vector field measurements of petawatt laser pulses, S Howard et al, Nature Photonics, 26 June 2025